Second seasons of television are always a risk. If the first is a success, then how do you move on, whilst trying new things? And if the first isn’t brilliant, how do we improve?

In 1995, both Fantastic Four and Iron Man changed animation studios and writing staff. The new executive producers for the second seasons had worked on the legendary 1980s Saturday Morning Cartoons as well, but had been raised on a later interpretation of the Fantastic Four’s run.

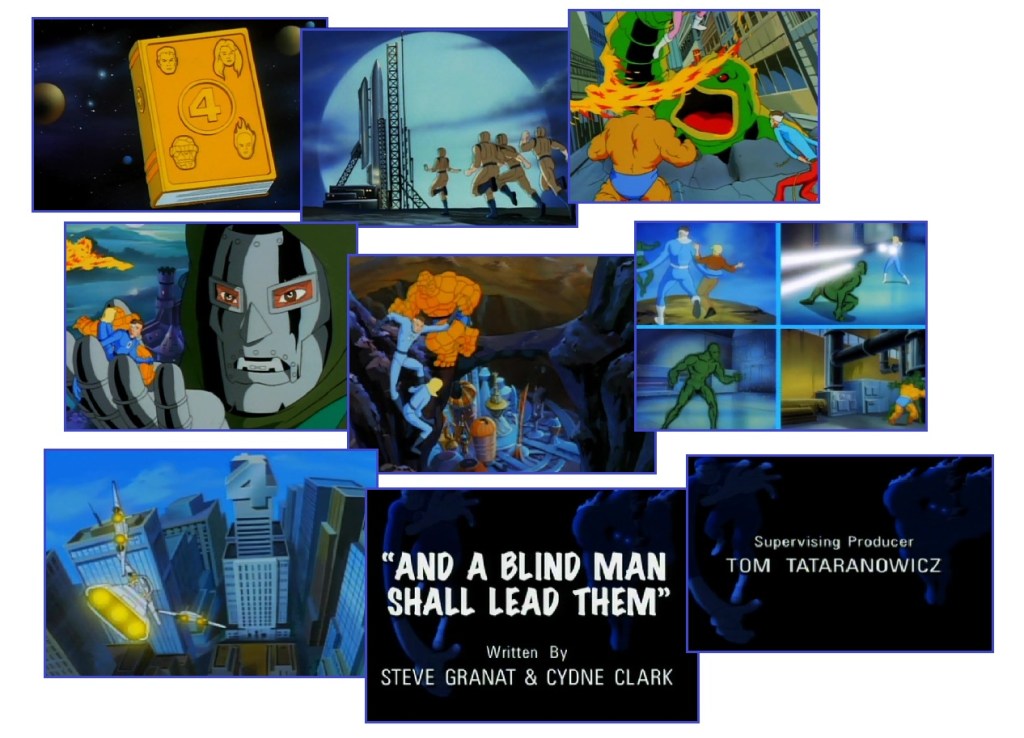

So, we open season two with an an episode about transition – between bases, between voices, between eras. It adapts Fantastic Four #39–40 with reverence but reinvention, threading in comic lore while testing new tonal ground. It’s a soft pilot for Daredevil and a recalibration of Doom’s entire presence.

But beneath the continuity shifts and production pivots, the emotional core holds: identity under pressure, trust forged in vulnerability, and the quiet heroism of getting back up when the powers are gone. It’s not just a crossover – it’s a character study in disguise.

The Baxter Building looms for the last time, a monument to what the Fantastic Four were before the fall. This isn’t just a new season – it’s a rupture. Powers lost, roles inverted, and the team forced to reckon with who they are when the cosmic fades and the human remains. Into the breach steps Daredevil: blind, brilliant, and burdened with his own mythology. He doesn’t just guide them – he redefines the stakes.

Doctor Doom returns, but he’s evolved. His voice is richer, his language more ornate, his menace now laced with gravitas. He’s no longer just a villain – he’s a sovereign force, reshaped by performance and prose. The explosion that opens the episode isn’t just spectacle – it’s a signal. The Pogo Plane is already ash, and the Baxter Building is about to be history.

And somewhere in the rubble, a blind man leads the way.

An island, mid battle. On a sandy beach, Mr. Fantastic, the Human Torch and the Thing battle an army of purple clad robots. Underneath their feet, held prisoner in an impenetrable field of his own technological design, Doctor Doom has Susan Richards captive. In an effort to alert her teammates to where she is, the Invisible Woman makes the ceiling above her invisible – and Ben Grimm spots her. Breaking through to Sue, the Fantastic Four watch as Doom makes his escape. But he’s left a trap – as soon as he leaves, and unable to stop it in time, the entire island is engulfed in a nuclear blast – and the Four are caught in it.

Rescued at sea, the Four return home, only to find that their powers are gone! The nuclear reaction has removed their powers, transforming Ben back to his human self! He actively starts to enjoy his former life, even preparing to propose marriage to Alicia, but he finds himself frequently nervous.

Reed Richards, aware of the danger they’re in if Doom discovers they are powerless, begins to create technology that can duplicate their powers. But at the same time, Doctor Doom attacks.

Saved by the intervention of Daredevil, the Fantastic Four are helpless as Doom takes control of the Baxter Building‘s tech, unleashing Reed’s own weaponry and science against them. As Daredevil travels to Doom in order to distract him, the others ascend the Baxter Building, manoeuvring through Doom’s traps.

Eventually, Doom is almost triumphant, until Ben, using a device Reed has built to restore their powers, sacrifices his new happiness and becomes the Thing again. He battles Doom to a stand still and crushes the Monarch’s hands, defeating him in shame.

As the Four thank Daredevil for his help, they are unaware that he’s Alicia’s friend, blind lawyer Matt Murdock, who she and Ben had visited earlier that day.

But the damage is done. The Baxter Building is toast. The Fantastic Four are currently homeless!

The second season was completely redesigned and overhauled with this premiere. It features a new set of opening titles, showcasing missions from the Four’s comic book history. Their origin, their first battle with Doctor Doom, and the hidden city of Attilan are all depicted. A title card now credits the writer and director before the action begins.

This season was taken over by animation legend Tom Tataranowicz, whose first credited work in animation was He-Man and the Masters of the Universe. He also served as executive producer on Iron Man and The Incredible Hulk, with many crossovers between the two.

The Fantastic Four were caught in an island explosion in Fantastic Four #38 – courtesy of the Frightful Four. In this episode, Doom is behind it, but the Frightful Four make their series debut in the very next episode.

The rest of the episode is based on Fantastic Four #39-40, and even shares the same title: “And a Blind Man Shall Lead Them.”

The Baxter Building makes its final appearance in this episode, and is replaced in the next by their 1990s base, Four Freedoms Plaza.

Brian Austin Green has left his role as the Human Torch and Johnny has been recast. He’s now voiced by Quinton Flynn, who will reprise the role in Spider-Man.

The Fantastic Four’s Pogo Plane is seen – and destroyed – at the start of this episode. In the comics, it first appeared in Fantastic Four #38 – the same issue that the opening teaser of this episode is based on.

Daredevil appears in this episode as a test for the character, to see if he could carry his own animated series. The series never materialised. However, the Fantastic Four are the first Marvel superheroes Daredevil ever represents, taking them on as clients in Daredevil #2.

From Season One to Season Two, Doctor Doom has evolved into far more than just a villain in a mask. His language changes in this episode – he’s far more loquacious than before, with a sense of pomp and gravitas added to his performance. This is partly due to the excellent writing, but also thanks to the voice recast of Simon Templeman, who reprises the role in The Incredible Hulk and later this season.

As a result, Doom gets the best lines in this episode. He hilariously calls Daredevil a ‘Primrose Popinjay’ and, as he’s escaping for his life, he mentions it’s a shame he’s leaving New York so soon – as he “never did get around to seeing ‘Cats’.”

THE MAN WITHOUT FEAR

Matt Murdock’s origin is pure Marvel alchemy: radioactive ooze, a selfless act, and a boxer’s son raised in the crucible of Hell’s Kitchen. Blinded but gifted with heightened senses, Matt trains under Stick, a grizzled mentor with secrets of his own. By day, he’s a lawyer with a conscience. By night, he’s Daredevil – the Man Without Fear – armed with billy clubs, Catholic guilt, and a moral compass that bends but never breaks. His first issue in 1964 sets the tone: justice isn’t clean, and heroism isn’t painless.

In the wider Marvel tapestry, Daredevil is the connective tissue between street-level grit and mythic consequence. He’s fought alongside Spider-Man, clashed with the Punisher, and stood toe-to-toe with gods and monsters. But his real battles are internal – faith, trauma, identity. Frank Miller cracked him open in the ’80s, and Bendis, Brubaker, and Zdarsky kept the wounds fresh. He’s a loner who builds found families, a vigilante who believes in the law, and a man who keeps getting back up, no matter how many times the world knocks him down.

The 1990s flirted with giving Daredevil his own animated series – a pilot was drafted, concept art floated, and his appearance in Fantastic Four was a litmus test. The tone was darker, the cast ambitious: Elektra, Kingpin, even Namor. But the series never launched. Maybe the networks balked at the moral complexity, or maybe the timing was off. Either way, Daredevil became the great “what if” of Marvel animation – a character too layered for Saturday morning, but too iconic to ignore.

Still, he left fingerprints. His guest spots in Spider-Man: The Animated Series and Fantastic Four proved he could hold the screen. The voice work varied, but the gravitas remained. These weren’t just cameos – they were narrative probes, testing whether audiences could follow a hero who doesn’t quip his way out of trauma, but wrestles with it in silence.

And now? He’s ascended. Charlie Cox’s portrayal in the Netflix series – and now the MCU – cements Daredevil as mythic, modern, and emotionally raw. He’s the first Marvel hero to lose everything and still choose grace. No cape, no shield, no billionaire tech. Just a man, a mask, and a promise: to protect the broken, even when he’s breaking too.

The Silver Surfer and the Return of Galactus | The Inhumans Saga (Part 1): And the Wind Cries Medusa

Leave a comment