Now this is how you launch a series.

No origin story. No drawn-out spider bite or the murder of Uncle Ben. That’s all saved for deeper into the mythology. But this opening chapter has so much to accomplish, it’s a wonder it doesn’t buckle under its own web.

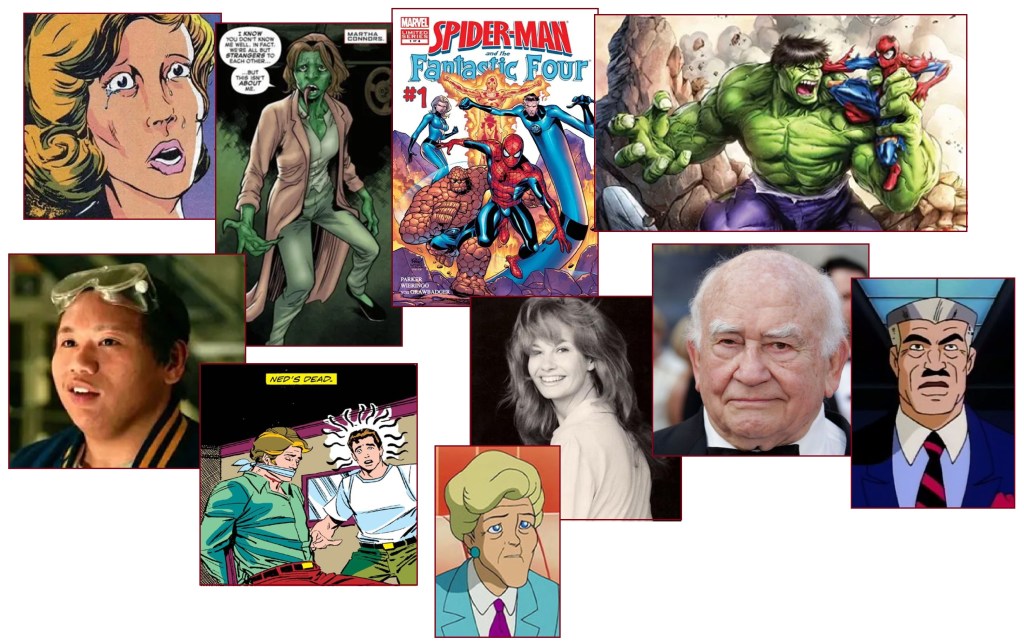

And yet, it works. Aunt May, Jameson, Robbie, and Peter step straight out of the comics — notably the John Romita Sr. era — and into our hearts. The Lizard gets a strong showing: a sympathetic villain who yearns for acceptance, but will settle for dominance over rejection. He’s cold, merciless, and monstrous — counterbalanced by the softer, resolute Curt Connors, whose only real flaw is being a damn good teacher.

It’s tragic, then, that Eddie Brock — introduced significantly early here — will go on to weaponise that goodness. His attempt to damage the Connors family for the sake of his own reputation is an early sign of how dangerous this version of Brock can be, even without the symbiote. It puts him on a collision course with Spider-Man before he’s even aware of it.

The animation is sublime — distinctive for its time, blending early CGI with traditional artistry. It’s colourful, confident, and doesn’t waste time setting the table. Everything you need to know about Peter Parker and Spider-Man’s world is laid out with precision by series writer John Semper.

An introduction to a world that, for many of us, we never truly left.

Beneath the streets of New York, a routine inspection turns into a nightmare. Two service workers are attacked by a monstrous reptilian figure. One vanishes into the dark, the other escapes — only to spiral into hallucination, haunted by the creature’s glowing eyes. His panicked flight through the city ends with a near plunge into the river, stopped only by Spider-Man’s intervention.

At the Daily Bugle, whispers of the Lizard reach Peter Parker. Robbie Robertson shares the story, while J. Jonah Jameson offers a thousand-dollar reward for photographic proof — sparking a bitter rivalry between Peter and Eddie Brock. Back home, Peter discovers Aunt May has been hiding overdue bills, shielding him from the weight of their financial troubles.

Tracking giant footprints in the subway, Peter heads to Empire State University to consult Dr. Curt Connors. But Connors is nowhere to be found. Instead, Peter and Debra Whitman witness the Lizard escaping with a large, wrapped device. Later, at the Connors home, Spider-Man finds Eddie Brock under attack. He drives the creature into the sewers, only to learn the truth from Margaret and Billy Connors: the Lizard is Curt, transformed by the Neogenic Recombinator — a device meant to regrow his lost arm, now twisted into something far more dangerous.

Eddie, eavesdropping, is swiftly webbed to a lamppost. But the Lizard seizes Margaret and vanishes underground. Spider-Man follows, locating the missing service worker and confronting the creature. The Lizard reveals his plan: to use the Recombinator to transform Margaret — and eventually the entire city — into humanoid reptiles like himself. In the ensuing struggle, Spider-Man activates the device mid-battle, reverting the Lizard back into Curt Connors.

By morning, Eddie Brock attempts to expose Connors, only to be humiliated when the scientist answers the door in human form. Peter, meanwhile, uses the reward money to help Aunt May — a quiet act of heroism in a city that rarely sees it.

ROGUE’S GALLERY

THE LIZARD

Dr. Curt Connors was once a brilliant biologist and war veteran, driven by the noble goal of restoring his lost arm. In his pursuit of regenerative science, he created the Neogenic Recombinator — a device capable of rewriting genetic code. But in merging his DNA with that of a lizard, Connors birthed something monstrous. The Lizard first appeared in Amazing Spider-Man #6 (1963), a creature of cold intellect and primal instinct, whose desire for acceptance curdled into a hunger for domination. He is not merely a villain — he is a tragedy in motion, a man eclipsed by his own ambition.

Across comics and screen, the Lizard has remained one of Spider-Man’s most emotionally charged adversaries. From animated adaptations to cinematic reimaginings, his duality — the gentle teacher and the ruthless predator — continues to haunt Peter Parker. Whether stalking the sewers or threatening the city with forced evolution, the Lizard embodies the cost of unchecked science and the fragility of identity. He is a monster born of hope, and a reminder that even the best intentions can spiral into horror.

The opening credits of the series, with it’s catchy “Spider-Man, Spider-Man, Radioactive Spider-Man,” is performed by Aerosmith’s lead guitarist Nick Perry.

This episode boasts many first appearances of Spidey’s supporting cast: J. Jonah Jameson, Robbie Robertson, Eddie Brock, Aunt May, Curt, Margaret and Billy Connors and Debra Whitman. All recur more than once throughout the series.

Jonah’s Jibes: His “You want it cooked or raw?” when Eddie Brock offers to eat the Bugle if Connors is proved to not be the Lizard. Connors is misspelt ‘Conners’ throughout the episode.

Gerry Conway was a huge Marvel comics writer who worked on Amazing Spider-Man #111-#149, directly succeeding Stan Lee.

Margaret is more commonly known as ‘Martha Connors’ in the comic books.

Thwip Quip: Spidey to the Lizard: “Good reflexes… for a handbag.”

Spider-Man mentions that the Fantastic Four are unlikely to be found in the sewers. He also references the Hulk, the Avengers and the Defenders.

Ned Leeds’ name appears on the Bugle’s front page. Ned Leeds, one of Peter’s closest friends, has a long and torrid history – and all of it confused with the Hobgoblin. He’ll appear briefly later in the series, in season four’s Guilty.

The voice cast of this series is one rightly praised. In this one episode alone, the legends are forming. Linda Gary, who voices Aunt May in the series up as far as season four, voiced Teela and Evil-Lyn, as well as many other roles in this writers’ favourite childhood obsession He-Man and the Masters of the Universe. Hank Azaria, who voices Eddie Brock, is much better known for his numerous roles on The Simpsons, which defined a generation or two. Edward Asner would be nominated for an Emmy award for his role as J. Jonah Jameson in the series.

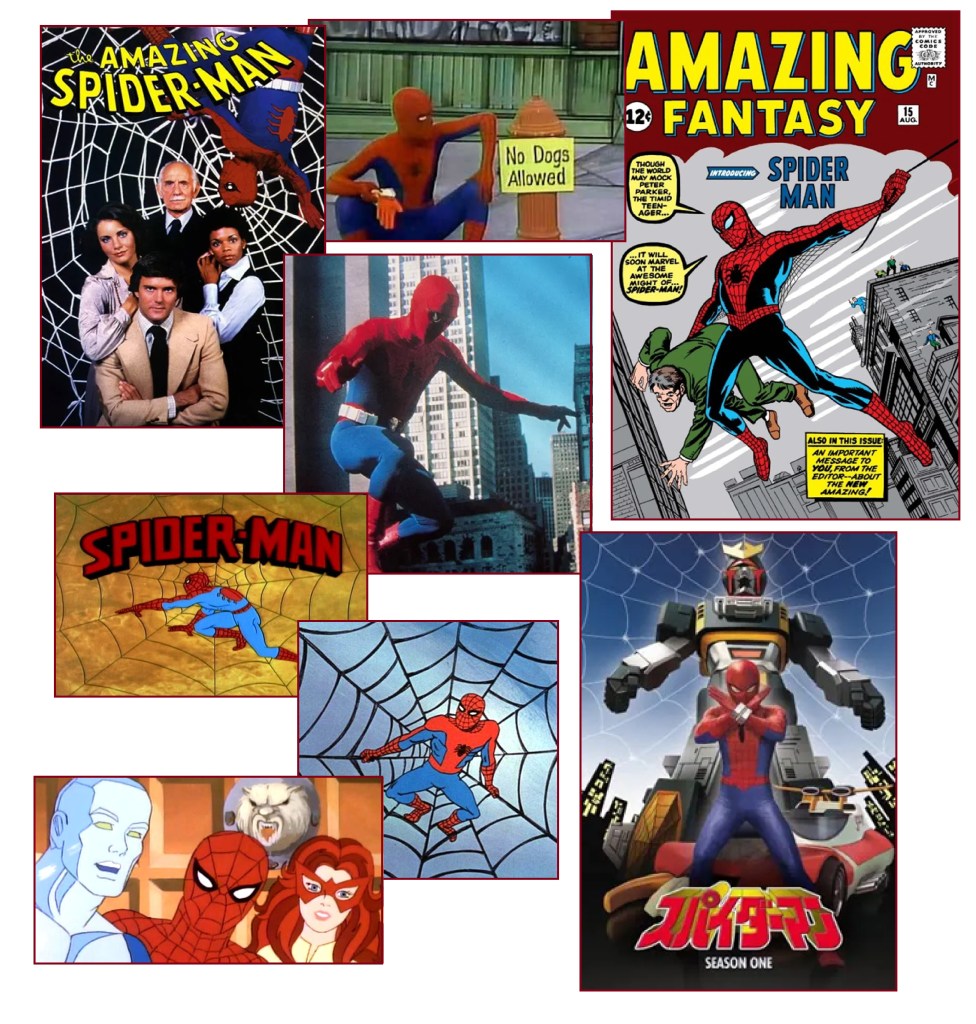

BEFORE THE WEB WAS WOVEN: PREVIOUSLY ON SPIDER-MAN

Before 1994, Spider-Man’s on-screen legacy was a patchwork of ambition, limitation, and earnest charm. His first appearance in comics — Amazing Fantasy #15 (1962), created by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko — introduced a teenage hero burdened by guilt, gifted with power, and destined for myth. But translating that complexity to screen proved elusive. The 1967 animated series, with its iconic theme tune and psychedelic backgrounds, captured the surface but not the soul. It was followed by Spidey Super Stories (1974–77), a live-action segment on The Electric Company, which leaned into educational skits rather than narrative depth.

The late ’70s brought The Amazing Spider-Man (1977–79), a live-action CBS series starring Nicholas Hammond. Though ground-breaking in its attempt to bring Peter Parker to life, it was hampered by budget constraints, limited effects, and a reluctance to embrace the comic’s rogues gallery. Internationally, Japan’s Supaidāman (1978) reimagined the character entirely — a tokusatsu hero with a giant robot and alien origin — a cult classic, but far from canonical. The 1981 animated Spider-Man and its companion series Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends (1981–83) brought a Saturday morning charm, but often sidelined Peter’s emotional core in favour of team-ups and moral-of-the-week storytelling.

By the early ’90s, Spider-Man’s screen presence was fragmented — a collection of half-remembered theme songs, ropey wirework, and simplified morality. What Spider-Man: The Animated Series offered was something different: a commitment to long-form storytelling, emotional continuity, and a rogues gallery that felt dangerous, tragic, and mythic. It was the first time Peter Parker’s duality — the tension between responsibility and desire, guilt and heroism — was given room to breathe across seasons.

The series didn’t just adapt comics; it honoured them. It wove together threads from The Night Gwen Stacy Died, The Alien Costume, The Clone Saga, and Kraven’s Last Hunt, all while introducing a generation to characters like Felicia Hardy, Morbius, and Madame Web. Its animation may have been limited by budget, but its ambition was limitless — a show that dared to treat its audience as capable of following arcs, feeling loss, and questioning heroism.

In a decade where superhero media was still finding its voice, Spider-Man spoke clearly. It wasn’t perfect, but it was sincere, serialized, and steeped in legacy. For many, it was the first time Spider-Man felt real — not just a cartoon, but a character who could break your heart and still swing into the sky.

Leave a comment